🔗 From Plastic to Pixel: How AI Memes Memorialize Mediums

When a new image-generation technologies become mass entertainment, what makes it meaningful?

Marketing science tells us distinctive assets work as memory cues and recognizable shortcuts that drive brand choice in buying moments.

What happens when those assets aren't brand-led logos or colour palettes, but the individual content users themselves create from generative AI?

The recent launch of Nano Banana, Google's newest upgrade to Gemini's image generator, and its subsequent content output, offers a curious line of thinking into how ‘prompt memes’ are assets that create symbolic value for new AI led technology brands and their emergent mediums.

Within days of its release this summer, Chinese social platform Rednote was flooded with posts sharing a remarkably uniform format: a miniature figurine sitting in front of its packaging box and a desktop monitor displaying the modelling process.

The individual figurines themselves range from anime characters (Jinx from Arcane, Sailor Moon) to users' own pets (#turning-my-cat-into-a-figurine) and projective mini-me's (#wedding-day-me). These figurines are customizable and take seconds to generate. But while the foreground content differs, the backdrop remains consistent across thousands of posts.

While the average user of Nano Banana may well focus on the foreground content of their miniature figurines – a 1/7 scale personal asset – it is the symbolic tableaux background that fascinates us, because their visual codes reveal insights about our relationship with evolving mediums and implications for how generative AI tools are marketed.

Memento Mori: a reminder of vanity and virtuality

In 'Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man' (1964), Marshall McLuhan observed that "the content of any medium is always another medium. The content of writing is speech, just as the written word is the content of print."[1]

The Nano Banana memes enact this principle visually: they present a stack of mediums, each containing the one before it. A figurine referencing injection-moulded plastic collectibles sits in front a screen displaying industry standards Cinema4D or Zbrush, which themselves reference the 3D modelling workflows that preceded generative AI.

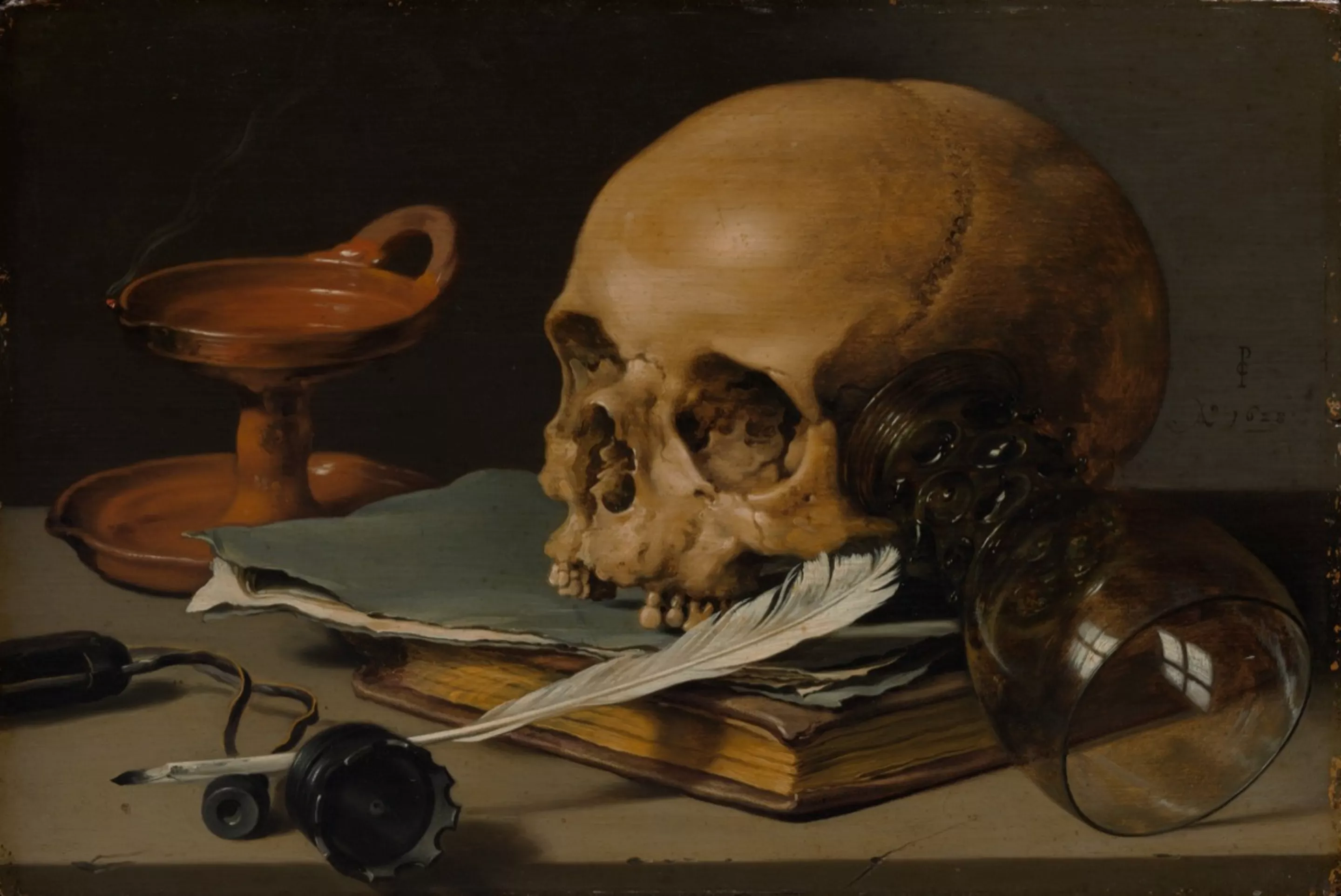

It's a lateral leap, but the composition and content of these memes remind me of the memento mori concept made popular in 17th-century Dutch still life painting.

Those compositions purposefully featured objects with decay built into them: ripening fruit, cut flowers, overflowing candles – as meditations on mortality and the passage of time. When present, human subjects, were juxtaposed against this objects, and often 'one step removed’ from reality; a portrait reflected in a mirror, a figure glimpsed through a doorway. At their most direct, human mortality was symbolized by a skull.

From a technical standpoint, these paintings showcased the 'technology' of their era. Complex to paint organic textures such as grape skins, flower petals, and iridescent shells demonstrated the painter's command of verisimilitude. Linear perspective, visible in the orthogonal floor tiling of Vermeer's interiors in paintings like ‘The Art of Painting’, illustrated mastery of spatial illusion and proportion of scale.

At the time of their creation, such techniques represented the cutting edge of image-making; verisimilitude was the marker of quality. Similar dialogues between representation and realism happen whenever new mediums emerge: from painting to photography, photography to moving images, moving images to computer generated images.

The Nano Banana memes perform a similar dialogue between representation and realism. If we look closely at the background: Maxon’s tools’ rectilinear perspective grids echo the rooms demarcated by Vermeer's tiles, but they're pushed back onto the monitor screen occupying the same compositional position as an antique map hung on the wall in those 17th-century interiors. Oblique perspective was a comment on an antiquated medium and associated worldview.

The layering of these mediums and tools in the Nano Banana memes frame current industry-standard tools: Cinema4D, ZBrush, Blender, Unreal Engine as potential future relics. The surface application is consumer facing fun, but the underlying threat is commercial displacement.

We also note the visual rhyme between the 'Claymation' aesthetic of the modelled figure on the screen and the objecthood of the memento mori skull. Both represent the human form reduced to material: the body without flesh or soul, rendered as inert matter.

It appears fitting that these memes frequently feature BANDAI figurines of animated IP like Sailor Moon and Dragonball Z, popular cartoon media from Chinese childhoods now replaced by avatars and gaming icons.

The memento mori framing reminded 17th-century viewers of their mortality. These memes, while attempting to convey reality, remind us of our virtuality.

Human countenance as last refuge

In the seminal ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1935), Walter Benjamin articulated how technical reproduction shifts art from cult value to exhibition value.

For Benjamin, photography’s displacement of cult value is resisted with the “ultimate retrenchment: the human countenance.”

As he poignantly wrote, “It is no accident that the portrait was the focal point of early photography. The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuse for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty. But as man withdraws from the photographic image, the exhibition value for the first time shows its superiority to the ritual value.” [2]

It strikes me that something similar is at play with these AI-generated figurines and ‘prompt memes’. In the early transformation to generative imagery, there is a typical aura.

Users interact with their sense of self via miniature models, avatars are placed before a chain of mediums and visual technologies that live out McCluhan’s ‘Laws of Media’ – enhances, obsolesces, retrieves, and reverses into. The figurines are surrounded by older image-making mediums: packaging boxes that reference physical collectibles, monitors displaying software interfaces, and family portrait photos.

Here, the miniaturised self becomes the new human countenance - a refuge for something like aura in an age of infinite generation.